The security guard at the front gate of Pune University campus instructed the taxi driver. I looked along from the taxi parked by the curb. The driver walked back to the car.

“He says that the new institute is at the back. It’s under construction,” the driver mumbled under his breath. He pulled the taxi door shut and drove into the campus. I rolled down the window.

The city was cool and fresh from the rain. It was the summer of 1991. The early morning bustle of a strange town always fascinated me. In the subconscious unease of the unknown, it comforted with a warm nostalgic familiarity. The sweepers cleaning the neighborhood. The children waiting for the school bus. People loitering around their favorite breakfast corner. Folks jogging. Fresh vegetables glistening in the first morning light. An old man lost in his cigarette smoke and the morning newspaper. A radio blaring at a distance. People, joyfully greeting each other. Everything seemed nice… We all woke up to the promise of a new day.

Through the unpaved road, we reached the back of the campus. The place was peppered with a few newly built houses and incomplete buildings. This time it was my turn to seek directions. I got out of the car and walked towards a house. Seeing me approach, a man dressed in white walked out of his house and smiled,

“Are you here for the exam?”

“Yes, but —” I could barely speak. I knew the man. I knew him long before I had seen him on TV. He used to provide his expert commentary right before the beginning of my favorite show, Cosmos, by Carl Sagan. The man was well-renowned astronomer Dr. Jayant V. Narlikar.

“–If you continue on this road, you’ll find the registration office. They will further guide you.” He said with a smile. He waved behind us as we drove in that direction.

Back then, the Inter-University Center for Astronomy & Astrophysics (IUCAA) and the National Center for Radio Astronomy (NCRA) were relatively new institutes. They conducted a joint entrance examination for students inspired and eager to pursue a career in the field. I was very interested in radio astronomy. I was deeply fascinated by the idea of ‘seeing’ the invisible universe. I still am. To my surprise, there were too many of us. I had just finished my astronomy summer school at the Indian Institute of Science, where I had the privilege of studying under the leading scientists. I was brimming with immature confidence.

At the summer school, I had come across an introductory brochure of NCRA. In which I had learned that NCRA was building the world’s largest radio telescope array. It was called the Giant Meter-wave Radio Telescope (GMRT). The meter-wave part meant that the telescope would search for extremely weak light coming from very distant objects (protogalaxies and protoclusters) that were in their early stages of the formation when the universe was very young. I was hooked for life.

The format of the admissions process was designed to eliminate in stages through written exams, interviews, and then the final interview.

I, luckily, passed the hurdles and reached the last interview. The interview was in a small office with a large window. I was ushered into the room. To my left wall was a large whiteboard. And huddled in the corner of the opposite wall by the window were four smiling gentlemen. One of them, whom I had already met, was Dr. Narlikar. To his left was another gentleman whose big, happy smile put me to ease right away. I gathered that he was from the NCRA part of the admissions committee. And to either side sat the other two men. I want to say that one of them was Dr. Kembhavi, but my memory is fuzzy on that. I nervously stood by the whiteboard. I had instinctively picked up the marker and was ready to write. After a brief introduction, the gentleman with a big smile started asking personal questions, mostly about my hometown.

He seemed to know the place quite well. He then explained that a part of his family was from my hometown. And once my nerves were calm, the ‘grilling’ began.

At some point through the barrage of questions, the discussion switched to the cosmic background radiation (CMB), the embers of the hot origins of the universe. These were pre COBE times, but the consensus was that CMB had a blackbody spectral signature. I had sketched the Planck’s blackbody curve on the board. That’s when the gentleman from NCRA, with the big smile, took charge of the discussion. He honed in on the y-axis of the plot that I had sketched.

“What is on the y-axis?” He asked.

“The spectral density,” I replied.

“Good. And what are the units?”

“Ah,” I fumbled and then wrote the units somewhat apprehensively.

More questions followed; precise and expertly designed questions, just to nudge an inquisitive mind into self-discovering deeper relationships between physical quantities, often taken for granted in textbooks. Led by hand through these equations, I suddenly ‘discovered’ that within the limiting case of the Planck’s law, the power from a distant object measured by a radio telescope was the same as its temperature. The radio telescope was a thermometer!

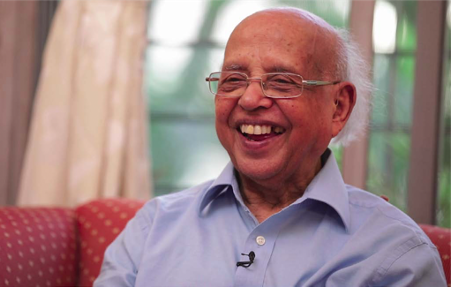

My sudden joy of discovery reflected brightly on the face of Dr. Govind Swarup. He had made me think differently about an issue that I thought I had understood. And this is how he made his first and lasting impact on me. In just a brief discussion, he taught me that the foundation of science is to never stop asking and investigating. There’s often more than meets the eye. Just with his few well-poised questions, he had elevated me from the books to the inextricably linked real world of the actual implementation.

Upon my return from Pune, one day, when my mom was busy with her daily chores, I followed her around the house, sharing with her my experience from the summer school and Pune. I excitedly mentioned how this one man who also asked me questions about my hometown had dazzled me by teaching me new ways of scientific inquiry. She nodded and left the room. A few minutes later, she returned with an old photograph of a young man and a woman.

“Was that professor this man?” She asked, handing me the picture.

I took the picture, a very young Dr. Swarup was smiling back at me.

“Yes!” I exclaimed, “How did–?”

“–Are you sure?”

“Yes, this is him… his younger self,” I reassured.

My mom was ecstatic. The lady in the photograph was Mrs. Bina Swarup, my mom’s long lost childhood friend.

And that’s how we all got reconnected with Dr. Swarup and Mrs. Swarup.

I did not get admitted to NCRA. I moved to the US to continue my education in radio astronomy and physics. Throughout the years, I stayed connected with Dr. Swarup.

During one of my trips to India in the late nineties, Dr. Swarup invited me to visit GMRT. Since the interview, this was the first time I was meeting him. At NCRA, I could tell that he was eager to show me his labor of love. He accompanied me to the telescope location, about 80 km from NCRA.

We survived the bumpy car ride and reached the remote site. At that moment, there were roughly thirty telescopes. Each was 45 meters in diameter. Up close, the telescopes were massive. The telescopes were arranged in a Y-shape across a 25 km area. The innovative design by Dr. Swarup had made GMRT one of the leading telescopes in meter-wave astronomy in the world. He told me that since the observed wavelengths were long, he designed the mesh-based dishes (radio antenna) instead of filled ones. This way, he saved the cost of metal per dish, and eventually, the total cost of the telescope.

The local village juxtaposed against the world’s largest telescope was a sight right out of India. I was working at Caltech in those days and had access to a similar, but smaller array right outside my office. I was quite impressed by GMRT.

At the young age of 67, Dr. Swarup’s zeal for science, especially radio astronomy, was contagious and inspiring. I stayed with him for the next few days. And just like the interview, this time, I got a priceless crash course in radio techniques from a world-renowned scientist who never made you think that he was one by his sheer humility and grace. Dr. Swarup was not only a scientist – he was an electrical engineer, a mechanical engineer, a leader, a mentor, a teacher, and forever willing to learn. He was a complete scientist. In today’s world of suffocating specialization, that was such a breath of fresh air.

Besides his friendly and kind demeanor, Dr. Swarup was blunt when needed. He did not like it when, out of tradition, to greet him, I used to touch his feet. And he did not like me calling him Dr. Swarup. Reluctantly though, I was able to forego the feet touching. But he is forever Dr. Swarup to me.

He tried to recruit me a few times, but I was happy far away. Again he never minced his words and with a laugh once said, “Raju ban gaya gentleman!” (Local lad has become a gentleman). Even his insults were inspiring.

We stayed in regular touch. Whenever I needed advice, he was available. When he learned that I was planning a brief trip to India, he invited me to GMRT again. I happily took the offer. I stayed over in Pune for a couple of days. These trips required giving a colloquium talk. Back then, I was working on a Dark Energy project and had enough material to share. After the talk, he handed me over to the other professors and suggested a time when I stop by his office and retire for the evening and dinner.

“I have something to show you. Stop by at 4:00, sharp,” he added.

I knocked on his door at 4:00, sharp. He invited me in. He seemed to be in a thoughtful mood. I assumed he was preoccupied.

But he turned to me and said, “Good talk. I have a question. Why at 1.8 z?”

I knew what he was asking. He was curious why Dark Energy suddenly seems to accelerate the universe after a random time (or z for redshift). I walked up to the board in his office, which was already cluttered with equations, and in the corner sketched the energy density vs. time (redshift) plot. It was quite a deja vu moment.

The y-axis of the plot was the energy density of the universe. I did not write the units. Now I was old enough to know that units were irrelevant. You could set them to whatever value that suited your needs. And the x-axis was time since the big bang. Then I drew the matter density. A curve starting high close to the origin and then decreasing as the time on the x-axis increased. Next, I drew a horizontal line parallel to the x-axis. And where the line crossed over the curve, I marked that point as 1.8 z. I did not say a word and turned to explain. I saw the familiar wide smile and a gleam in his eyes. I knew immediately that he understood what I wanted to say.

“This is one of the best explanations I have seen. OK!” He said.

I was proud to have shared my knowledge with him for a change.

Dr. Swarup had a way of returning to the main topic.

“Coming back, here’s something I wanted to show you.” He said as he took out a small black diary.

“Do you remember your first interview with us?”

This must have been more than a decade now.

“Yes,” I said.

“I took some notes that day. Read this.” He handed me the diary.It read (am paraphrasing)– he’d become an astronomer someday.

I was dumbfounded. I had no idea how to respond to this. I stood there quietly holding the diary. He then took out another slightly larger diary and opened it. This was his autograph collection book. He showed me many signatures of people that I knew. I recall seeing S. Chandrasekhar’s signature. Then he handed me a pen and asked me to sign the book. I couldn’t. Instinctively, I refused.

“Rubbish. Why not? This is my book.” He exclaimed.

“But… this has Chandra and so many others… I don’t belong here.” I grumbled.

“Just sign it.”

So I did.

This was his way of encouragement and guidance. He made you feel welcomed.

I met Dr. Swarup a couple of more times since. The last time I met him in person was when I was on a historical trip across India with my mom. We decided to stop over in Pune and meet with the Swarup’s. Dr. Swarup suggested that now I know enough radio astronomy to show my mom around GMRT. I did. My mom was quite impressed by the telescopes. During our stay in Pune, we tried all kinds of amazing street food with Dr. and Mrs. Swarup and had a blast.

In 2008, after many discussions, Dr. Swarup and I agreed to work on a long-overdue collaboration. He wanted to do something weighty, something exciting, or not at all. I was on the same page.

“Read up on WMAP Cold Spot and then we’ll talk,” Dr. Swarup directed.

In short, there’s a region of the sky, about 5 degrees (10 full moons) in size, which breaks away from the norm. It appears emptier than it should be. A survey of the region using radio telescopes indicated the same. This result had caught Dr. Swarup’s attention.

There were a few tentative explanations proposed in the scientific literature, including that it could be some form of data aberration. I raised this issue with Dr. Swarup, and his response was, and I paraphrase, “I did not build a telescope to use statistics to find my answers. Let’s go observe the thing and find it for ourselves.”

Using GMRT, we were able to corroborate the previous observational results. Later, the results from the Planck satellite further confirmed the existence of the cold spot. In other words, the mystery remains. But despite the best of our efforts, we were unable to complete the project to the extent that we had originally discussed and planned. This remained a point of our mutual dissatisfaction.

Time flew by, and before we could revisit our project, I was invited for the 90th birthday of Dr. Swarup that was celebrated by NCRA. Sadly, I was unable to attend. I decided to send my regards through flowers and a brief note entitled – The Serendipity Of Meeting Dr. Swarup. And not until a few months ago, to my horror, I discovered that the article got lost in the mail and never reached him. I started to rewrite this.

Today I woke up to an ominous morning. The sky was bright red due to the smoke from the fires all around the San Francisco Bay Area. That’s when the news arrived, my teacher, my mentor, my advisor, my guru ji Dr. Swarup had passed away.

The news was sudden and unexpected. It hit hard. I was already fondly reliving the past while rewriting this note. The loss became very personal and palpable.

I realize that now no one would be able to fill those shoes. But we all could aspire to walk the path defined by Dr. Swarup’s unbridled curiosity, passion for lifelong learning, taking on and completing larger than life projects, and most importantly, humility and respect for others. Dr. Swarup was a great scientist, but above all, he was a marvelous human. I’d die a happy man if I were a fraction of what he was.

It will forever remain a source of deep sadness for me that Dr. Swarup did not read this note that I wrote for him. I will deeply miss him all my life.